I don’t yet know all of what I’ll write about on this blog. The topics will probably be random, but will invariably lead to speculative fiction, Dungeons & Dragons, Tolkien, writing, publishing, and maybe snippets of real life. But since this is a public site, I don’t think I’ll be talking about the private lives of family and friends.

Today I’m going to talk about gnomes.

Dungeons & Dragons gnomes, specifically. Because why not? I spend just as much time thinking about imaginary worlds as the real one, and gnomes occupy one little corner of all worlds. Gnomes, and other fantasy creatures and monsters, are my Roman Empire.

Fun fact #1: In his early Middle-earth writings (as in, pre-Hobbit and pre-Rings), Tolkien called one particular group of elves Gnomes. They were later renamed the Noldor. They were the crafty variety of elves, the ones who liked mining and shaping gems. Here’s a footnote from The Book of Lost Tales, Part One, concerning the word ‘gnome’:

Two words are in question : (1) Greek gnōmē ‘thought, intelligence’ (and in the plural ‘maxims, sayings’, whence the English word gnome, a maxim or aphorism, and adjective gnomic); and (2) the word gnome used by the 16th-century writer Paracelsus as a synonym of pygmaeus. Paracelsus ‘says that the beings so called have the earth as their element . . . through which they move unobstructed as fish do through water, or birds and land animals through air’ (Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. Gnome2).

Fun fact #2: When I first pitched my Eberron novel to Wizards of the Coast in a closed call (the novel that eventually became The Darkwood Mask), I had a female gnome as my main character. (Formerly an artificer assigned to a Brelish battalion in the Last War, now she now desired to become an investigative reporter for the The Korrenberg Chronicle, the most popular broadsheet, or newspaper, on the continent.) The Eberron editor didn’t think a short character like a gnome—or halfling or dwarf—could “carry” the story. (Bilbo might disagree, but I’m not Tolkien.) So I had to work up new heroes (they became a human and a half-elf). It all worked out in the end, since I’m still proud of the book as is.

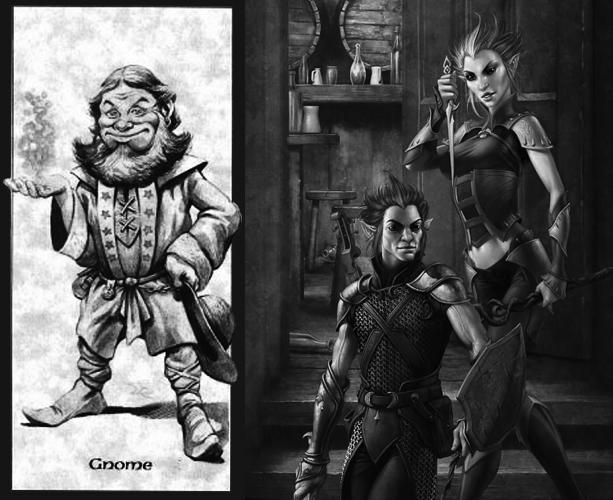

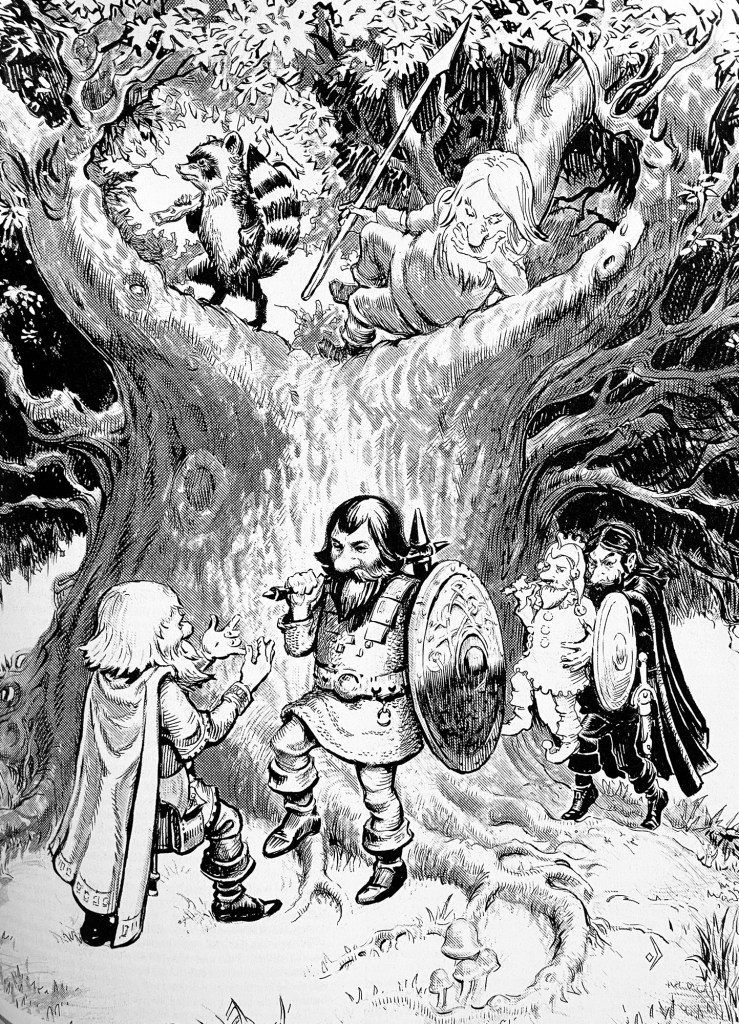

So, gnomes. Through most of their history in the game, gnomes were assigned a comical and silly aesthetic, and kind of looked like what you’d get if you squished a halfling and a dwarf together. That’s not a complaint. Gnomes have been fun. From the svirfneblin (deep gnomes) to the tinker gnomes of Dragonlance, and every subrace in between (like forest gnomes and rock gnomes), they are usually small, sometimes even smaller than halflings, with large bulbous noses, beards, and at times sported the conical hats we associate with garden gnomes.

In the early Advanced Dungeons & Dragons years, there weren’t a lot of physical descriptions of any races/species. The designers were more interested in rules and tactics—perhaps because the hobby was still closer to its wargaming roots. Players’ imaginations were meant to fill in whatever the books didn’t cover—guided, maybe, by illustrations provided. And gnomes were presented as both a playable race and a “monster.” But they were usually good guys. Neutral or lawful good guys, that is. So if you weren’t playing one, if you met gnomes in your game you were probably helping them out (or they were helping you out). In older games, you were probably saving them from something.

Like . . . kuo-toa? Sure.

The Players Handbook (1978) and the Monster Manual (1977) only provided information about gnomes’ stats, organization, habitats, armor and weaponry, animal companions, etc. And as far as I can tell, the only physical description was to be found in the final paragraph of their MM entry:

Most gnomes are wood brown, a few range to gray brown, of skin. Their hair is medium to pure white, and their eyes are gray-blue to bright blue. They wear leather and earth tones of cloth and like jewelry. The average gnome will live for 600 years.

Deities and Demigods (1980) gave them their own god, Garl Glittergold. Dragon magazine issue #61 (1982) and the Monstrous Compendium (1989) gave us more about their culture, affinity for magic and especially illusions, and sense of humor, plus a little pantheon of deities over which Garl Glittergold presided. The Complete Book of Gnomes and Halflings (1993) is a gem of a book that dishes out even more cultural information to play with (and a lot pointy garden-hats). And there have been other articles and assorted bits about gnomes sprinkled throughout the 80s and 90s and early 2000s.

But, in my humble opinion, as a race, gnomes hit their unique magical and physiological stride in the 4th Edition of D&D, which hit in 2008. That is not an edition I normally praise too much—though in fairness, most of my freelancing for Wizards of the Coast took place during the 4E era. There were plenty of cool innovations and even lore inventions that did manifest in that edition, despite the many bits I didn’t like. (I’m leaving aside the whole matter of game rules.)

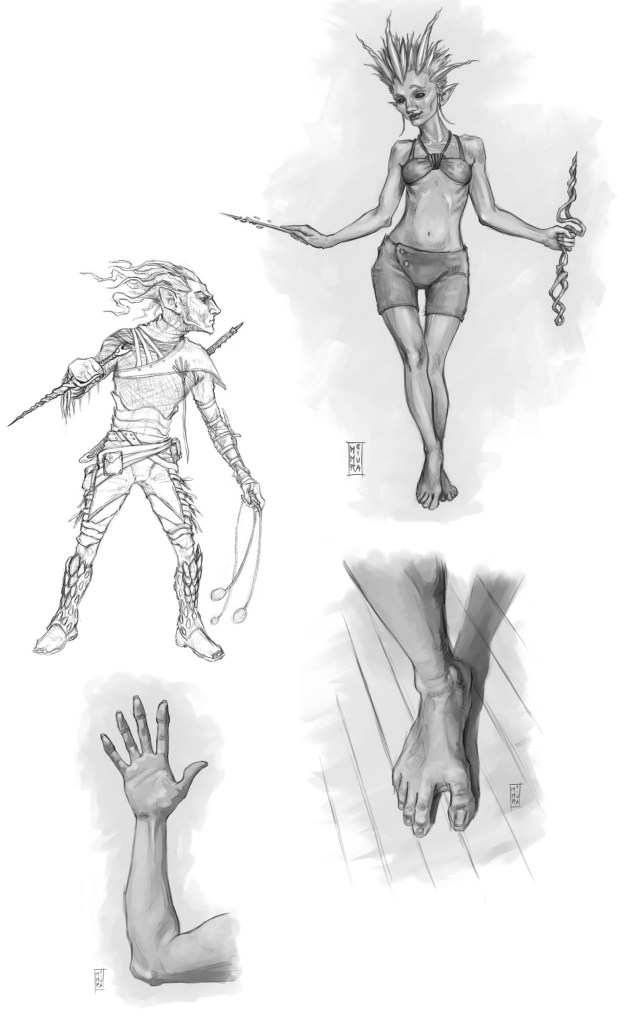

The concept sketches and color illustrations of artist Raven Mimura really sold the new gnome for me. Gnomes went from being an amusing and magic-flavored alternative to halflings or dwarves to something a little more . . . alien. And more distinct.

Aesthetically, intrinsically, they became even more faerie-like. Prior to 4E, faerie realms were just magical regions deep within a some forests or other wildernesses. And that was fine. In fact, the less defined the faerie world is, the more mysterious and powerful it is.

But the 4E system altered the entire cosmology of D&D from what it had once been. It invented some new planes, renamed some, fused others, and rearranging them all. This included the invention of the Feywild, which was another plane of existence, “an enchanted reflection of the world,” a place of arcane energy, beauty, and majesty. The Feywild became the dimension of origin for all fey creatures—eladrin, elves, dryads, pixies, sprites, hags, and the like. And of course, gnomes!

These races were now literally alien to the Material Plane. Now, I did like the idea of the Feywild, though I still feel some of mystique is lost by bordering Faerie so neatly. Now those deep wildernesses that you want inhabited by faeries can simply be said to overlap with the Feywild, and that’s how fey beings filter into the mortal world. That works, too.

In any case, gnomes in 4E became fully fey creatures; previously, they were classified as humanoid, which tied them to the mortal world naturally. This classification change helped justify gnomes new, odder appearance and their intrinsically arcane nature. They even now all had an ability called fade away—once per encounter, if they are hit, they briefly turn invisible. Appropriately faerie-like.

4E didn’t initially present gnomes as a PC race in the Players Handbook—which was shocking at the time and is hilariously parodied in this old video—because WotC thought players would prefer to play as badass tieflings and dragonborn (“Play a dragonborn if you want . . . to look like a dragon”).

They did eventually add gnomes to the list of Player Character races in the Players Handbook 2 the following year.

Meanwhile, my Eberron novel, The Darkwood Mask, was published in 2008 . . . three months before the 4E core rulebooks debuted, so the gnomes that do get mentioned in my story are firmly 3E gnomes. Which was fine: The gnomes of Eberron were awesome from the start and more flavorful than the default gnome at the time. Devious, clever, obsessed with secrets and knowledge almost to a fault. As a people they solve their problems with smarts: misdirection, manipulation, and magic when necessary.

Midway through my book, the female protagonist makes a stop at a field office of the Korranberg Chronicle as part of her investigation. She wants to dig through old editions of the Chronicle. Which allowed me to essentially invent Eberron’s answer to microfiche. The Chronicle is run almost entirely by gnomes because it’s associated with House Sivis, a gnome-only dragonmarked house (which bears the Mark of Scribing).

Oh yeah, and my male protagonist—a sort of former special ops soldier, now an outlaw—favors the “gnomish hooked hammer” as a weapon. He likes unconventional weaponry, dislikes the predictability of swords, and admires the gnomish design of a two-headed weapon with a military pick at one end and a warhammer on the other.

Gnomes and gnomish things are fun, in conclusion.

I don’t know what’s becoming of gnomes in the next iteration of D&D (effectively 6E). Their 5E iteration was . . . fine, a bit watered down, and, in my opinion, overshadowed by cooler versions of gnomes of the past. They felt once against sandwiched between halflings and gnomes and seem to have traits traditionally associated with one of those two. I’d say that, in general, they’re kind of an overlooked people in most Dungeons & Dragons worlds. In fact, in the Forgotten Realms, they’re called the Forgotten Folk.

Off the top of my head, I can’t think of a major gnome NPC or hero in the D&D multiverse (not that there aren’t some). Which is a shame. But maybe this is how gnomes prefer it.

I’d enjoy hearing about anyone’s gnome characters, though! Or how they’ve been used in various campaign worlds or homebrew settings.

2 responses to “The Forgotten Folk”

Great article, Jeff! Interesting background on DWM, too; that would have made for a intriguing change (though, for the record, I’m glad you made the change).

I played a gnome PC only once, a ranger, with a huge chip on his shoulder. It was a bonkers campaign that went off the rails pretty quickly. Kristopheles Twist was a member of a party who rescued an orphaned unicorn mare. Twist would ride the unicorn into battle after that, even up the stairs of buildings, to stab stuff. The DM was fairly indulgent. 😉

LikeLike

Great name for a gnome. Sounds like you gnomed right, within the parameters of the campaign.

LikeLike