This posts blends Dungeons & Dragons, religion, and today’s political climate—that last one being a topic I would like to generally avoid here. But this one eats away at me so I just need to work through it “out loud,” as it were.

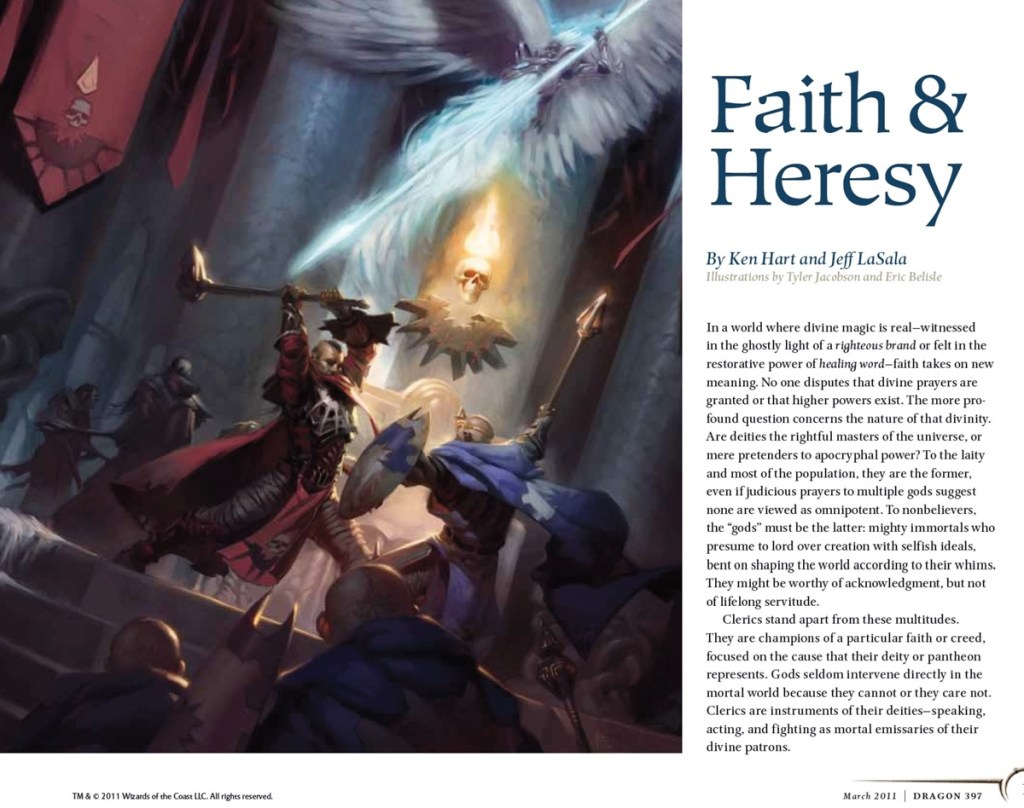

So, a long, long time ago while working in a career far, far away, I did a bit of freelance writing for Wizards of the Coast. At one moment in time, I got to cowrite (with my good friend Ken Hart) a D&D article titled “Faith & Heresy” (in Dragon issue #387 from 2011). It was essentially roleplaying advice for players or DMs and it proposed the idea that not all clerics, even those serving the same god, have to be the same, or even believe all the same things.

Every D&D gamer, whether longtime or newbie, tends to have their favorite class, race/species, or even type of adventure they enjoy playing in (or running). I mean it when I say that I enjoy dabbling in every kind of thing. I’ll take a dungeoncrawling game, an espionage or intrigue campaign, or a seafaring saga. I’m as happy with a totally mixed-bag party as I would be with a party of all monks, or all dwarves but of different classes. Oooh! Or an all-warforged party but each of the living constructs is from a different nation in the world of Eberron. How fun with that be? But yeah, if you twist my arm ever so slightly, I’ll admit that elves, rangers, golems, and gargoyles top the favorites list sometimes, as does gothic horror like Ravenloft.

But it must also be said that clerics, paladins, and gods in fantasy worlds have a special place in my heart. Theology in a D&D world doesn’t always follow the same “rules” as real-world theology—obviously—so it’s fun to play with. Put any campaign setting in front of me, be it homebrewed world or a long-established published setting like Greyhawk or Dragonlance, and I’ll be asking how the gods will be used. Even if the campaign has no cleric PCs, there should be NPCs aplenty who think about the gods. It matters to me what people in that world believe. Does the average person love them, hate them, or fear them? Maybe all of the above, depending on who you ask? What if they don’t think about them at all?

If you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice.

That’s fine, too. But I as a participant in that world—whether as a player or DM (but let’s face it, I’m always the DM—always want to know, for roleplaying and plot purposes. It matters to me, even if the matter of faith seldom comes up. Because believing in an afterlife, or the idea that souls might exist for the curation or protection of divine beings, should motivate people somehow. More immediately, it should affect their behavior in life somehow.

Just the same, my real-world theological ponderings and religious beliefs are part of the reason I like thinking about how faith might work in a speculative fictional world. First off, there’s no one way to depict religious practices and godly magic. It totally varies based on the principles and cosmology of the setting you make.

Take the Forgotten Realms. The gods of Toril are not only very real, there was a time in its history where the gods walked the mortal world in person, occupying powerful but killable avatars (a period known as the Time of Troubles, first written about in the Avatar series of articles and Avatar Trilogy). Therefore, in the Forgotten realms, you could possibly meet NPCs who literally interacted with a god in person. There’s no disputing the gods’ existence in the Forgotten Realms—only their intentions.

If you play in the Eberron campaign setting, the gods are indeed apocryphal, a bit more like our reality; no one’s ever seen the gods, no one can prove their existence, yet cleric and paladin spells are still granted to those who serve those deities or their interests properly. In Eberron, you can’t deny that divine healing magic works, but you can debate all day on the subject of who or what is really granting those spells. In fact, in Eberron, your alignment almost doesn’t matter if you go through the right motions in serving a particular god.

Where am I going with all this? I want to make an analogy with the real world, with what’s going on with those in power in the United States. This isn’t really about politics, only about those people entangled in the politics who claim to be religious—and in fact use it as a pretense to legislate their selfish worldviews—while demonstrating none of the virtue of their religion. That’s my gripe.

Going back to our “Faith & Heresy.” Early in our article, we clarified what clerics are in the D&D game, how they are agents of divinity.

They are champions of a particular faith or creed, focused on the cause that their deity or pantheon represents. Gods seldom intervene directly in the mortal world because they cannot or they care not. Clerics are instruments of their deities—speaking, acting, and fighting as mortal emissaries of their divine patrons.

We went on to address divine power itself, the path to heresy (even benevolent varieties of heresy), and even a way to roleplay defiance against one’s original god. Back in the old days of D&D (i.e. older editions), if you went against your faith, your god (and DM) could strip of your powers, deny you access to the cleric spells you once had. But later editions removed this, for game balance reasons, so that once ordained (once you were officially a cleric), you had your spells granted no matter what. Given that, in our article, we proposed the concept of introducing false prophets into your campaign. Maybe one of the players could be one, and maybe that could even be roleplayed as a good thing:

Let’s assume your female half-orc once worshiped Gruumsh, the chaotic evil god of slaughter and destruction. Having forsaken her formerly villainous ways, your adventurer now uses her divine magic to oppose the willful havoc that the One-Eyed God represents. She fights fire with fire (sometimes literally), wielding destructive energy through prayers that she acquired from her ordination. Such a “straying” character can expect a colorful menagerie of orcs and destruction-themed enemies to come against her, seeking retribution. Alternatively, consider a cleric of Vecna. To your friends at the gaming table, your lawful good cleric has a sunny disposition and shows

compassion for the oppressed. Consider their surprise when they learn that your cleric’s deity is—was?—the Maimed God. Suddenly your character becomes much more interesting.

In any case, one of the main points is, you can have different interpretations of a god, different practices, or even some differences on the core tenets of a god’s faith. Two clerics who worship the same deity might be part of different sects; they might consider each another odd, or off-putting, or even dangerous. How fascinating it might be if two players in a D&D campaign are like that. Wouldn’t it be neat if an adventuring party had both a paladin and a cleric who serve the same deity but are from two different temples and have some different interpretations of their god’s tenets. I for one would find that fascinating and fun to explore within the campaign’s plots . . . because it’s just a game and no one’s getting hurt.

Have a look at the awesome illustration that was paired with our article, a painting by Tyler Jacobson (who did the cover art for both the 2014 and 2024 core rulebooks!). The illustration was also used for the cover of that particular issue of Dragon magazine:

The illustration depicts clerics of Erathis—the “unaligned” (i.e. neutral) 4th Edition goddess of civilization—fighting one another. See the symbol these combatants wear? Erathis’s holy symbol is supposed to be a blue gear with a star inside of it, but notice how one faction of clerics in this image has their gear flipped vertically, the gear itself is spiky, and there’s a skull within it? Yikes! And whose side is that descending angel on?! Did one faction summon it, or did the goddess herself send the angel to settle this dispute? Someone’s gonna get a beat-down, either way. It’s so cool.

In real life, this would not be so fun. (But maybe it would be gratifying for some.)

But why are clerics of Erathis fighting one another at all here? It’s vague yet evocative, leaving us to imagine, like the best type of D&D art does. Our “Faith & Hersey” article put forth a batch of ideas that might explain this situation, though. See, in the 4E Players Handbook, concerning Erathis, we’re told . . .

She is the muse of great invention, founder of cities, and author of laws. Rulers, judges,

pioneers, and devoted citizens revere her, and her temples hold prominent places in most of the world’s major cities. Her laws are many, but their purpose is straightforward:

- Work with others to achieve your goals. Community and order are always stronger than the disjointed efforts of lone individuals.

- Tame the wilderness to make it fit for habitation, and defend the light of civilization against the encroaching darkness.

- Seek out new ideas, new inventions, new lands to inhabit, new wilderness to conquer. Build machines, build cities, build empires.

Imagine a lawful good PC cleric of Erathis representing those ideals wherever possible. Being good, she encourages cooperation and community and, whenever her adventuring party goes into wild places, she tries to bring comfort and the benefits of civilization to the natives. Maybe, if she’s being a bit pushy, she might even encourage said natives to relocate into civilization. Being lawful good, she shouldn’t be aggressive about it or force anyone’s hand. She should try to reason with the natives or demonstrate the virtues of civilization. She definitely shouldn’t be violent.

But given real-world history, it isn’t hard to imagine another cleric being more forceful, is it? My 11-year-old son recenty learned about the Trail of Tears in school, about the unjust displacement of so many native Americans. About the violence. It’s all too easy to imagine things going wrong from aggressive colonials, isn’t it? Let’s say there’s a neutral- or even evil-aligned cleric of Erathis (hopefully an NPC) who goes about imposing civilization upon those he deems too savage. The two clerics in these examples are sure to argue about the means, if not the core principles, of their goals.

We offered a bunch of example “heresies” in our article, using the main faiths of 4th Edition (because that’s just when this was written). So for Erathis, we had:

“All must understand that civilization is the only salvation.” Establishing and enforcing the rule of law is essential, according to this sect. Yet in some clerics’ eyes, forces of chaos lurk restlessly on the far side of the city walls. Those clerics take an overtly aggressive stance, promoting or leading forays into hamlets and tribal lands, demanding that the residents embrace the “protection” of the neighboring city. Any who resist are marked as enemies of civilization and must be slain.

The compassionate cleric of Erathis would be horrified by that. Is compassion part of Erathis’s faith? We don’t know. I guess that’s up to the DM and players in their campaign. But at least it’s easier to understand Jacobson’s illustration.

Let’s take another from the 4E gods. Let’s take Corellon Larethian, the god of spring, beauty, and the arcane arts. The tenets of his worship are normally . . .

- Cultivate beauty in all that you do, whether you’re casting a spell, composing a saga, strumming a lute, or practicing the arts of war.

- Seek out lost magic items, forgotten rituals, and ancient works of art. Corellon might have inspired them in the world’s first days.

- Thwart the followers of Lolth at every opportunity.

Now imagine if there was a sect of Corellon’s worship that took things several steps further, a sect that so revered ancient relics of the past that its members are . . .

determined to safeguard beauty forever, offering themselves as eternal guardians. This goal can be achieved only by crossing over into undeath.

Such a “heretical” cleric of Corellon might condone, say, the eventual embrace of lichdom—or of creating mummy servitors—so that they could better protect holy artifacts? This would be appaling to normal clerics of Corellon, especially elves (Corellon traditionally being the primary elf god in older editions, and elves usually hate undeath). So if two clerics of Corellon meet, one from this sect, and one from another, they would be at odds. They would debate the tenets of their god. They might even eventually come to blows or matters of imprisonment if they feel the other is a threat.

But at least, in this scenario, both would agree that one should cultivate beauty in all its forms, that arcane magic is an art as well as a tool. They might just disagree about the best way to serve Corellon’s interests in the mortal world.

BUT . . .

And here I’m finally getting closer to my point . . .

What if a sect of Corellon arose that claimed the best way to serve the god of spring, beauty, and the arcane arts was by promoting the season of fall, ugliness itself, and the disuse of arcane? magic? Instead of encouraging verdant growth, they actively withered plant life when they encountered it; instead of seeking out beauty, they actively mutilated things that were already lovely; instead of using the arcane arts, they quelled it wherever they found it, maybe even ostracized or rounded up known arcane magic-users? Is this group of Corellon followers merely interpreting spring, beauty, and the arcane arts differently? Would anyone buy that? Or would you think . . . I don’t know, they’re not really into Corellon at all but just like to say they are for some other gain?

Let’s take one last example, one I think would be a closer mirror to the real world.

In the Forgotten Realms there is a deity named Ilmater. He is known as the Crying God, the deity of endurance, martyrdom, perseverence, and suffering.

Ilmater offers succor and calming words to those who are in pain, oppressed, or in great need. He is the willing sufferer, the one who takes the place of another to heft the other’s burden, to take the othet’s pain. He is the god of the oppressed and unjustly treated.

llmater is quiet, kind, good-spirited, and slow to anger. He appreciates a humorous story and has a rather rustic humor himself. When his avatar appears, he takes assaults upon his person passively and rarely lifts a hand against another. He is not totally nonviolenr, though, as many often assume by his doctrine of endurance. When facing cruelties and atrocities his rage can boil up, and then he is a figure of frighteningly righteous wrath. His appearance can frighten the young, but he takes great care to reassure them as he treasures children and all young creatures, taking exceptional offense at those who would abuse or harm them.

Imagine what a cleric, paladin, or even monk in service to such a deity would be like—should be like. A player in an old game of mine was a cleric of Ilmater. He roleplayed it well, in part because he was such a decent human being in real life. Kerwyn of Arabel healed PCs and NPCs alike (sometimes even enemies, to the dismay of his allies); he advised peace; he took burdens and damage on himself on behalf of others. Yet he wielded his morningstar at need, in defense of others. A quintessential painbearer, as Ilmater’s “specitalty priests” are called.

I even made a business card for him, as a joke.

So here’s a scenario.

Let’s say there’s a particular NPC in the Forgotten Realms, a wealthy duke born in comfort and privileage. His inheritance gave him some power and influence, and he used his gold to step on others, swindle the poor, and con both impoverished and wealthier people out of their gold so he would have more. Then one day he aspires to be more than just rich. His pride and fragile ego now insisted that he become a king, maybe someday an emperor. But he couldn’t do it alone; he needed a populace to support his claim to kingship. He needs people to rule.

What if what allowed the duke to gain the support of so many people was the sponsorship of several large temples of Ilmater? These temples claim they wish to make Ilmater’s worship the kingdom’s official religion; all other faiths would be outlawed, and their temples either converted to razed. The goal is to impose Ilmater’s tenets of mercy and good-will on everyone. Anyone doesn’t fall in line will be punished or cast out. Oh, and nonhumans need not apply. Elves, dwarves, gnomes, halflings need to get out. This series of temples insists Ilmater only protects humans.

So why might these temples be supporting the duke? Does he somehow exemplify Ilmater? The duke is actually well known to be vulgar, bigoted, petulant, arrogant, insecure, cruel, humorless, and unquestionaly narcissitic. He is a bully whose actions often instigate violence; his actions cause suffering, they never alleviate it. BUT, check it out . . . There’s a rumor going around that the duke did once look in the vague direction of a temple of Ilmater and, when asked if he himself actually followed the Crying God, he didn’t say “no.” That’s all the high priests needed to hear. So they back him up, knowing his rise might fill their halls and their coffers. Most of the followers in the land are insisting that the duke is Ilmater’s chosen one, too.

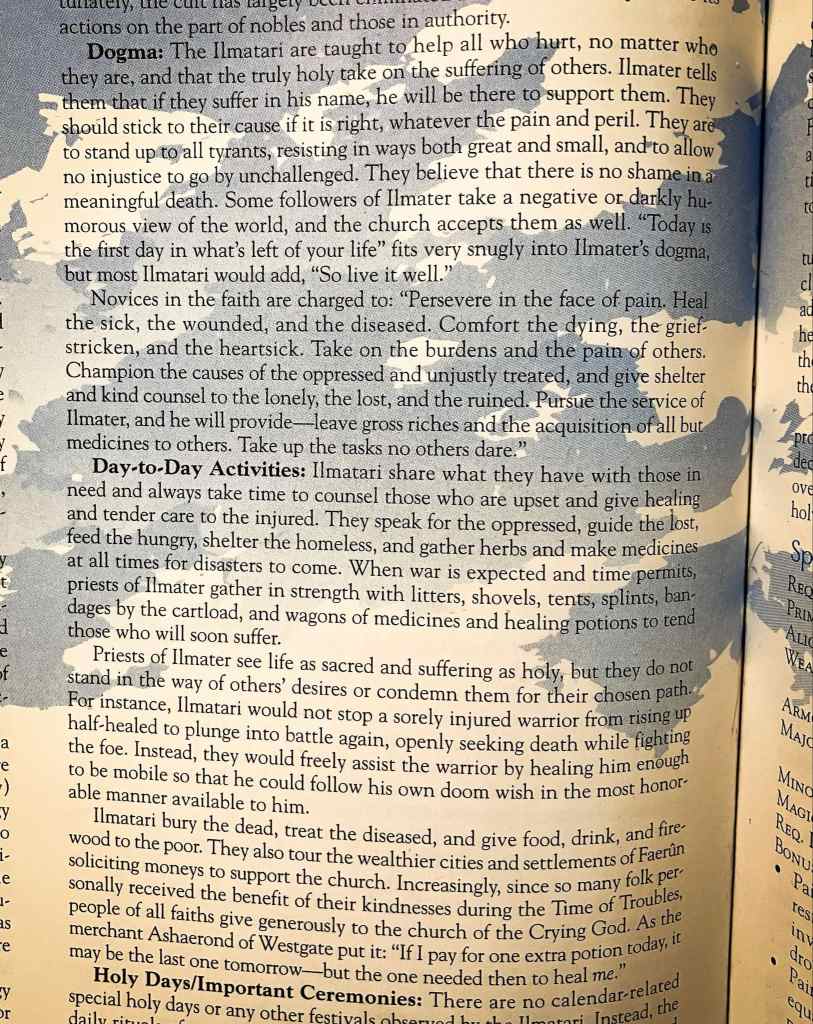

Let’s review what it means to be one of the Ilmatari, i.e. the followers of the Crying God. This is straight out of Faiths & Avatars, a 2E book, which means within the Forgotten Realms, this is like a summary of their Scripture.

Yet somehow the duke is supported by a lot of people claiming to “help all who hurt, no matter who they are,” who are supposed to “take on the burdens and pains of others,” to “champion the causes of the oppressed and unjustly treated.”

Here’s a question: If we don’t like this duke and don’t want him usurping the kingship, should we be angry at the temples backing him, and at those so-called priests and lay followers, or should we be angry at Ilmater himself? In this scenario, plenty of temples of Ilmater exist elsewhere outside the kingdom, who actually live and observe the Crying God’s dogma, and they don’t like this duke at all. In fact, there are a growing number of angry painbearers among them who wish to oppose this new movement.

Funny enough, in a D&D setting (well, some), you could simply watch and see if any of the duke-supporting Ilmatari clerics can actually cast spells. That could be evidence of whether they’re in the right or in the wrong. That is, are their magical prayers being granted? If not, well, that’s the answer; Ilmater doesn’t support them. If they can cast spells, the question then becomes: is Ilmater letting them get away with their actions anyway (in which case we might be side-eyeing Ilmater, after all) or is someone else granting their divine power?

It’s apalling, of course, that a religious group claiming that one should ease the suffering of the less fortunate should be the ones actively oppressing the already less fortunate. To be instructed by their god to give food to the hungry but, at every turn, they take and take. To pretend to support life, but do what they can to deny it. The hypocrasy of such people makes it impossible to believe them.

They shout about love, but when push comes to shove

They live for the things they’re afraid of

I have no solid conclusion to make. I’ve just been thinking out loud in fantasy world terms as a way of working through my frustrations about the real world. Speculative fiction is a good place to suppose how things might play out if some of the names are changed.

As I’ve done many times before.